An Introduction into Combative Behaviour in Dementia Care

Imagine facing a situation where the person you're caring for, someone you've come to know and cherish, suddenly doesn't recognise you. Instead of a smile, they greet you with a look of confusion, fear, and sometimes aggression. For many professional caregivers and healthcare staff, this isn't a rare occurrence; it's a daily reality. Statistics tell us that up to 50% of people with dementia will exhibit aggressive behaviour at some point, especially as their condition progresses (Dettmore et al., 2009). Caring for someone with dementia is complex. Staff members are not just caregivers; they are confidants, protectors, and often the bearers of compassionate continuity in the lives of those who can no longer remember yesterday or recognise today. Acknowledging the skill and patience of these caregivers is crucial. It's about recognising the human element in the caregiving profession — understanding that behind every professional demeanour is a person who feels deeply, who takes home their worries and triumphs, and who requires support to continue performing their vital role.

Understanding Combative Behaviour in Dementia Care

To truly support the staff who deal with combative behaviour in dementia patients, it's important first to understand the root of these actions.

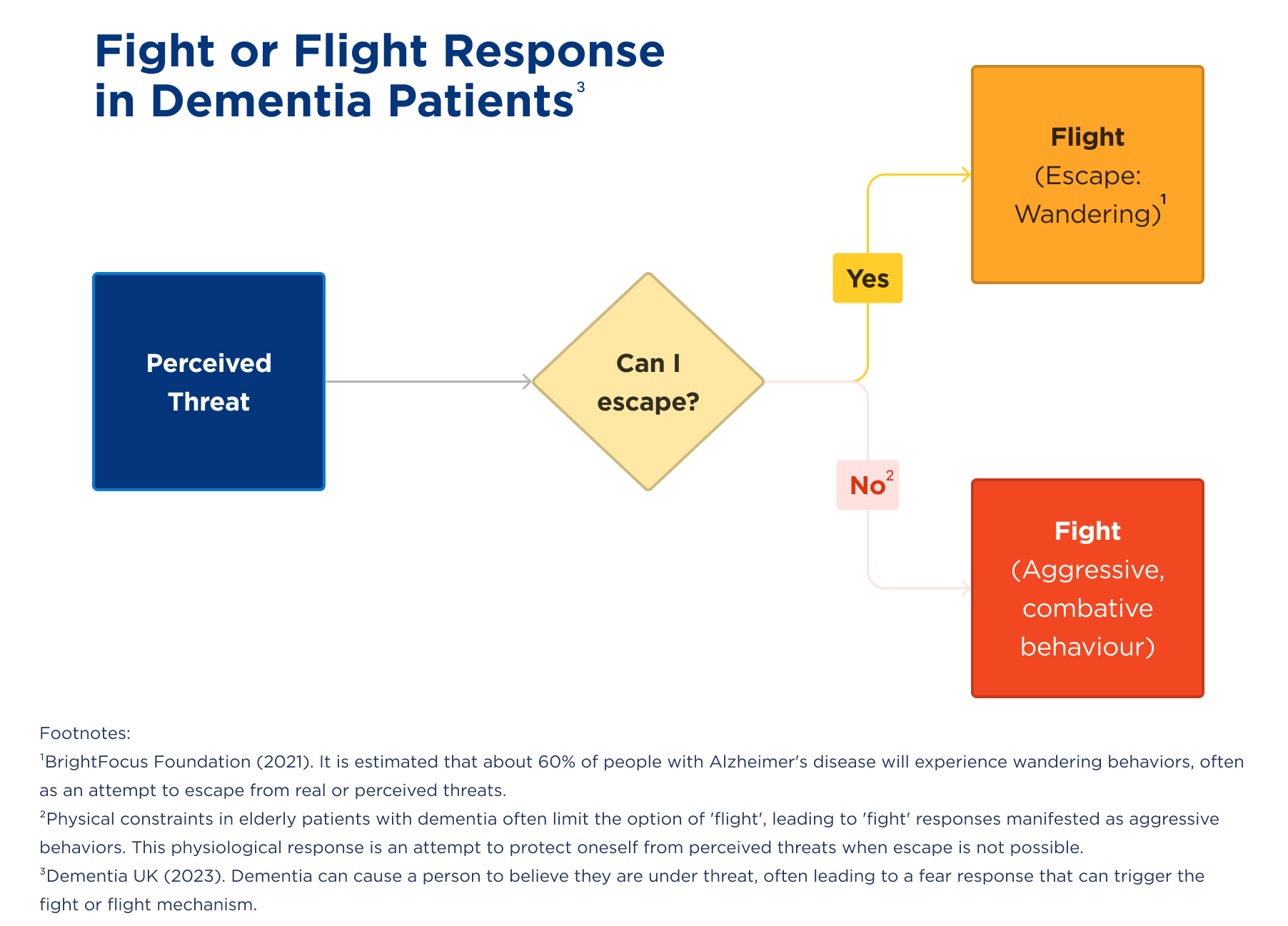

Automatic Fight or Flight Response

Dementia can be severely disorientating as it can impair a patient's ability to process their surroundings and communicate their needs. This confusion can result in fear that is as real to them as it would be to anyone facing an actual threat. Because of this, the automatic physiological response of fight or flight can be triggered (Dementia UK, 2023). As dementia often affects mainly the elderly, many of them will be limited by physical constraints, meaning that flight is not always an option in response. This results in fight being the physiological response, often experienced as aggression and lashing out. It is also important to note that the fight or flight response is also one of the key reasons as to why many dementia patients wander. BrightFocus Foundation (2021), a nonprofit funding Alzheimer’s research notes that a common reason for wandering is attempting to escape from a real or perceived threat and that this is estimated to affect 6 in 10 people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Unmet Needs

Aggression in dementia patients may also stem from a basic human need that goes unmet (Alzheimer's Society, n.d). Needs can range from the basic, such as hunger, thirst, or the need for rest, to the more complex, such as feelings of loss regarding their freedom or social life (National Institute on Aging, n.d). Pain is another common trigger; when a patient can't articulate physical discomfort, this frustration can lead to aggression. These behaviours may include biting, hitting, or yelling and can stem from an attempt to communicate these unmet needs.

Challenges Faced by Care Staff

Physical Harm

The risk of physical harm is a challenge for those caring for dementia patients who have instances of aggressive behaviour. Bites, scratches, and blows can all cause potentially serious injuries, and they all hurt! Biting can lead to serious complications as human bites to unprotected areas of the body frequently become dangerously infected, requiring immediate medical attention. This can lead to professionals being hesitant in their care work or needing time off work to recover. This can impact the worker, patient, and care system.

Emotional Stress

Emotional stress can be caused by the aggressive incidents themselves, the high-pressure environment, and the emotional rollercoaster that comes with caring for individuals who, due to their condition, may not always remember the helping hand extended to them. This stress is compounded by the heartache of witnessing the gradual decline of patients they may have grown to care for deeply, all the while managing the expectations and emotions of families entrusting their loved ones to their care (Sörensen & Conwell,2011).

Burnout

The culmination of the challenges caregivers face can often lead to burnout (Baker et Al., 2015). Signs of burnout among staff can include physical exhaustion, detachment, reduced performance, and sometimes even questioning their career choice. Burnout can drastically reduce the satisfaction that comes from working in caregiving and can lead to absenteeism and high turnover rates, which can negatively impact patients and care providers.

Strategies for Dealing with Combative Behaviour

Understanding the challenges is one aspect, but equipping care staff with the right strategies to handle combative behaviour is equally as crucial.

Before you begin trying to de-escalate an incident of aggressive behaviour, make sure that you are safe. This may mean keeping your distance, calling social services, or the police (Alzheimer's Society, n.d).

De-escalation Tips:

- Stay Calm: Keeping a calm and composed demeanour can have a calming effect on the person with dementia. Panic can fuel aggression, whereas calmness can act as a neutraliser.

- Non-Threatening Body Language: Use non-threatening body language. Keep a relaxed posture and maintain distance.

- Speak Softly and Reassuringly: Use a soft, reassuring tone of voice. Even if the individual does not understand your words, your tone can make a difference – by not raising your voice you are helping not to intensify the situation.

- Redirect and Distract: Redirect the person's attention to a different activity. This can help in calming down and distracting from the trigger of the incident.

- Identify Triggers: Learn and recognise triggers for each combative patient. By avoiding known triggers, caregivers can often prevent aggressive behaviour before it begins. After every incident of aggressive behaviour, detailed notes should be made on the circumstances around it and what steps of de-escalation were taken.

- Ensure Basic Needs Are Met: Check for discomfort, pain, hunger, thirst, or the need to use the restroom — addressing these can sometimes alleviate the reason for aggression by making the patient more comfortable.

- Personal Space: Respect personal space while assessing the situation; invading personal space can increase agitation.

For more information on dealing with combative behaviour in patients, please visit guidance from the Alzheimer's Society in the UK and the Alzheimer's Association in the US – both of which have 24/7 helplines.

Protective Clothing for Dementia Caregivers

When preventative strategies and communication are not enough to avoid aggression, protective clothing can play a vital role in safeguarding caregivers. BitePRO® offers garments designed to protect care staff from bites and scratches, common forms of injury in these settings.

Benefits of adopting BitePRO® protective clothing in dementia care:

- Enhanced Safety: By wearing protective clothing, staff can safeguard themselves against skin breaks and infections, which can result from bites and scratches.

- Increased Confidence: Knowing they have this layer of protection can help staff feel more confident in their interactions with patients, allowing them to provide care without hesitation.

- Stress Reduction: The peace of mind of wearing protective clothing can significantly reduce the anxiety of working with individuals who may become combative, lowering overall stress levels.

- Focus on Care: With the concern of injury lessened, caregivers can focus more on the quality of care and compassion they provide rather than being preoccupied with potential harm.

Protective clothing serves to complement the strategies of de-escalation and effective communication, creating a safer environment for both staff and patients.

For those dedicated to ensuring safety for professionals in caregiving, take a moment to explore the BitePRO® clothing range and learn how proactive, protective measures can make a difference at your organisation.

Sources:

Alzheimer's Society. (n.d.). Aggressive behaviour and dementia. Retrieved November 7, 2023, from https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/symptoms/aggressive-behaviour-and-dementia

Alzheimer's Society. (n.d.). Preventing and managing aggressive behaviour in people with dementia. Retrieved November 7, 2023, from https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/symptoms/preventing-aggression

Baker, C., Huxley, P., Dennis, M., et al. (2015). Alleviating staff stress in care homes for people with dementia: protocol for stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial to evaluate a web-based Mindfulness-Stress Reduction course. BMC Psychiatry, 15, Article 317.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0703-7

BrightFocus Foundation (2021) How to Prevent Wandering in Alzheimer’s Patients

https://www.brightfocus.org/alzheimers/article/how-prevent-wandering-alzheimers-patients#:~:text=Escape%20from%20a%20real%20or,made%20worse%20by%20some%20medications.

Dementia UK (2023) Keeping safe when you care for someone with dementia

https://www.dementiauk.org/information-and-support/living-with-dementia/keeping-safe-when-you-care-for-someone-with-dementia/

Dettmore, D., Kolanowski, A., & Boustani, M. (2009). Aggression in persons with dementia: Use of nursing theory to guide clinical practice. Geriatric Nursing, 30(1), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2008.03.001

Hansen, B. R., Hodgson, N. A., Budhathoki, C., & Gitlin, L. N. (2020). Caregiver Reactions to Aggressive Behaviors in Persons With Dementia in a Diverse, Community-Dwelling Sample. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 39(1), 50-61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464818756999

National Institute on Aging. (n.d.). Coping with Agitation and Aggression in Alzheimer's Disease. Retrieved November 7, 2023, from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-changes-behavior-and-communication/coping-agitation-and-aggression-alzheimers

Sörensen, S., & Conwell, Y. (2011). Issues in dementia caregiving: effects on mental and physical health, intervention strategies, and research needs. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(6), 491–496. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e31821c0e6e